The Bias–Variance Trade-off: Finding Balance in Machine Learning

Machine learning is all about building models that make accurate predictions on unseen data. But every model makes errors — and understanding where those errors come from is the key to building better systems. The bias–variance trade-off is one of the most fundamental concepts in machine learning, and it explains why models underfit, why they overfit, and how to strike the right balance.

The Bias–Variance Trade-off Explained

Machine learning has become the engine behind many of today’s most powerful technologies, from voice assistants to fraud detection systems. Yet even the most advanced models are never perfect — they make mistakes. Understanding why models make errors is one of the first steps toward improving them, and that’s where the bias–variance trade-off comes in.

This concept is one of the central pillars of machine learning. It explains why some models perform too poorly to be useful, why others seem perfect during training but collapse in the real world, and why the best solutions often live somewhere in between.

Why Models Make Errors

Every prediction made by a model is an estimate of reality, and there are always differences between those estimates and the truth. Statisticians and computer scientists have shown that we can break down model error into three parts:

- Bias – the error from overly simplistic assumptions.

- Variance – the error from being overly sensitive to training data.

- Irreducible error – the background noise in the data that no model can ever completely remove.

The relationship is often written as:

The first two — bias and variance — are the levers we can control. The last one is simply part of reality.

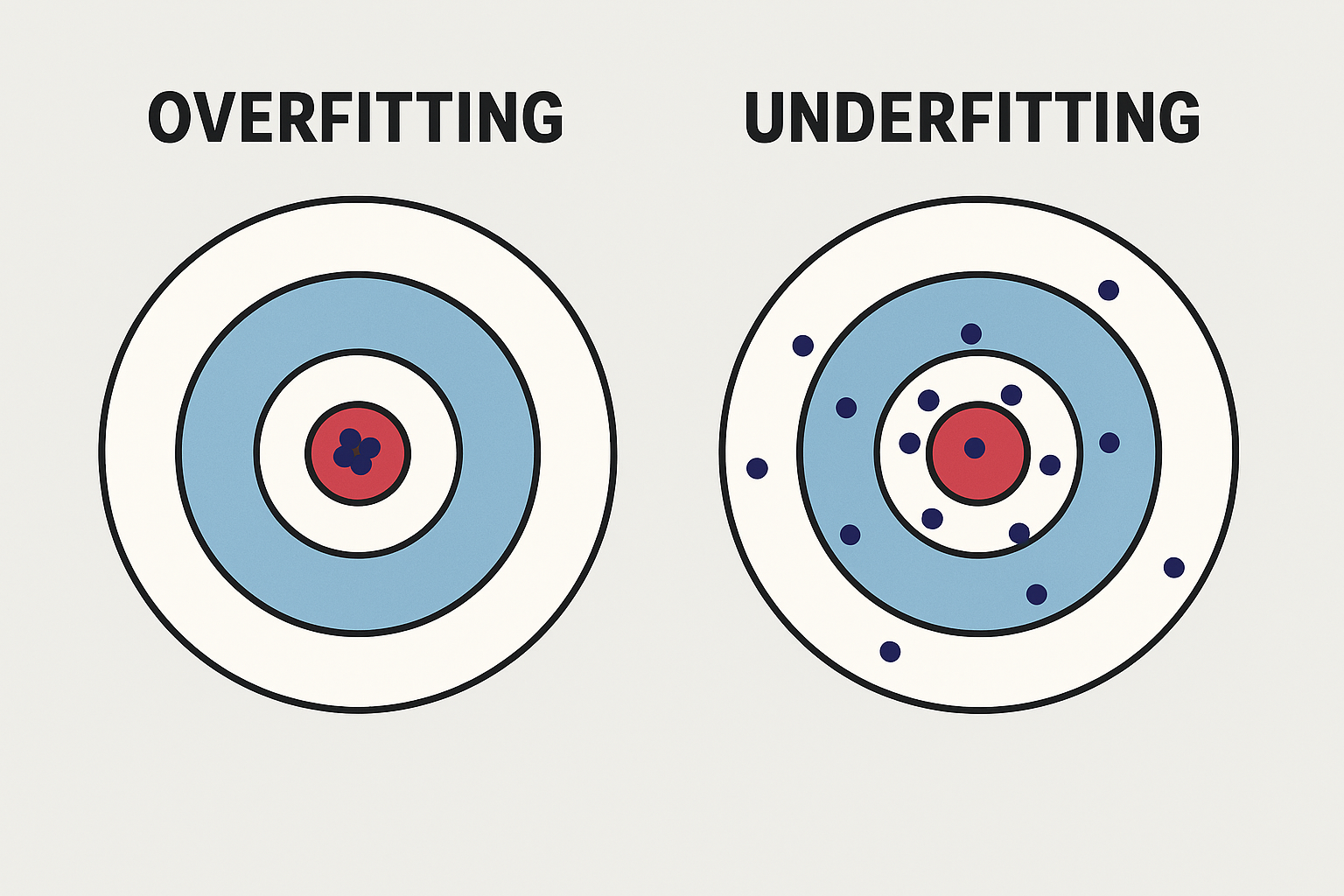

Bias: When Models Are Too Simple

Bias occurs when a model makes assumptions that are too simplistic to capture the real patterns in the data. Imagine trying to fit a straight line through data that clearly follows a curve. The line will miss important details, no matter how much data we feed it.

In practice, high-bias models tend to underfit. They produce poor predictions both on the training data and on new, unseen data. For example, predicting house prices using only square footage, while ignoring location or the number of bedrooms, would lead to a biased model that oversimplifies reality.

Variance: When Models Are Too Sensitive

If bias is about oversimplification, variance is about over-complication. A high-variance model adapts too closely to the training data, capturing not just the true patterns but also the random noise.

The result is overfitting. Such a model might achieve near-perfect accuracy on the training set but fail miserably when confronted with new data. A classic example is a deep decision tree that splits until it memorizes the training set, or a neural network without regularization that “remembers” data points instead of learning general rules.

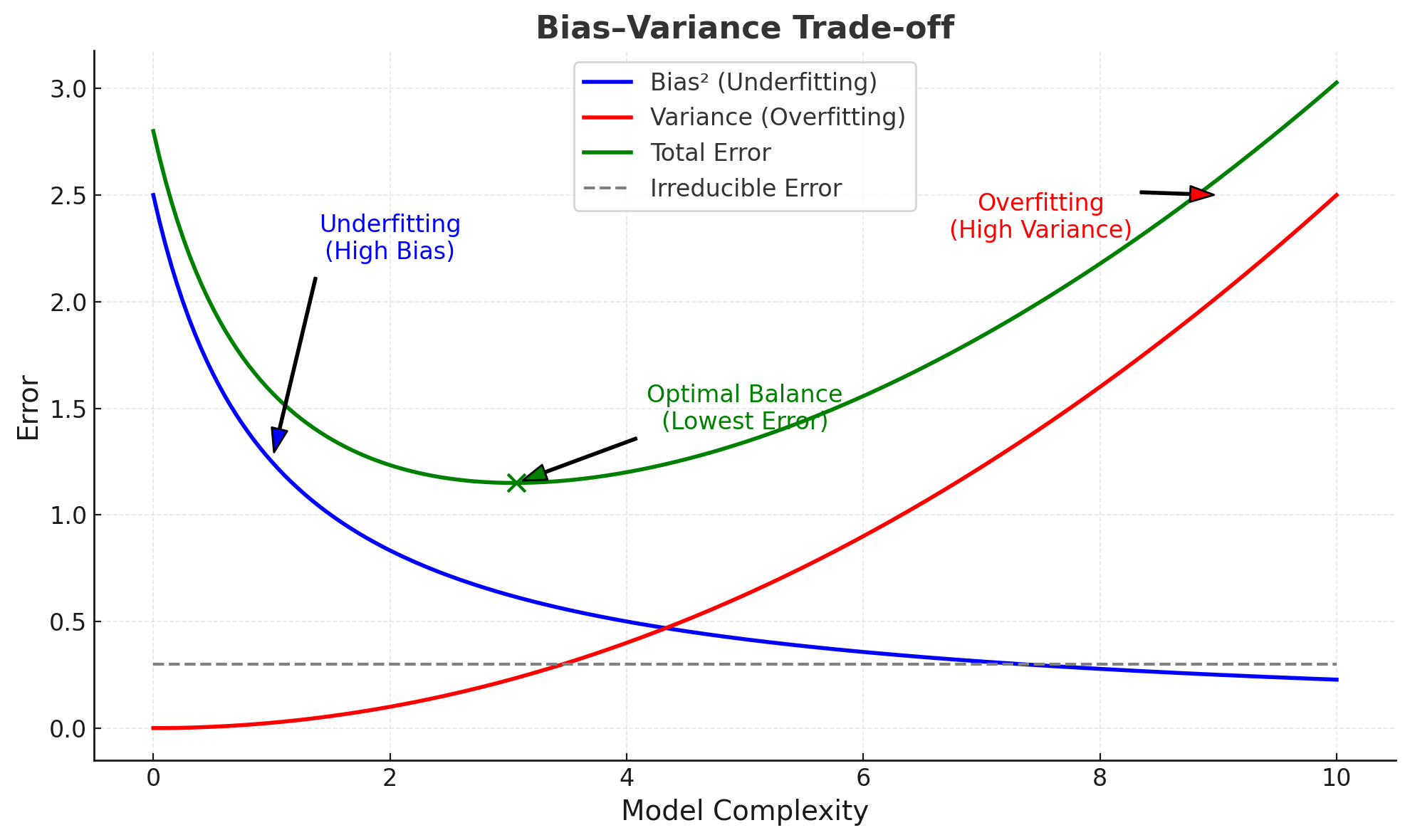

The Trade-off

Here’s the challenge: bias and variance pull in opposite directions.

- Simple models: high bias, low variance.

- Complex models: low bias, high variance.

The goal is not to eliminate one or the other but to find the sweet spot where the total error is minimized. This balance point is what allows machine learning models to generalize — to perform well not just on data they’ve seen, but also on data they haven’t.

Diagnosing Bias and Variance

How do you know whether your model is suffering from high bias or high variance? The answer lies in comparing training and test performance:

- High bias (underfitting): poor results on both training and test data.

- High variance (overfitting): excellent results on training data but poor results on test data.

- Balanced: strong performance on training data and nearly as good on test data.

Cross-validation is one of the most effective tools to spot these issues in practice.

How to Fix It

The strategies for reducing bias and variance differ:

To reduce bias (combat underfitting):

- Increase model complexity.

- Add more relevant features.

- Choose more flexible algorithms.

To reduce variance (combat overfitting):

- Gather more training data.

- Use regularization techniques (L1, L2, dropout).

- Apply ensemble methods such as bagging or boosting.

The art of machine learning lies in balancing these approaches.

Example in Python

To illustrate the trade-off, let’s run a simple experiment in Python. We’ll generate noisy quadratic data and fit models of different complexities to see how bias and variance behave.

Typical output:

- The linear model (degree=1) underfits: high bias, low variance.

- The complex polynomial (degree=10) overfits: low bias, high variance.

- The moderate polynomial (degree=3) strikes a balance: bias and variance both low.

This experiment shows the trade-off in action and why finding the right level of complexity matters.

Conclusion

The bias–variance trade-off is more than a theoretical curiosity. It is a practical framework that guides nearly every decision in machine learning: which model to choose, how to tune hyperparameters, when to gather more data, and how to avoid overfitting.

At DASCIN, we believe that mastering concepts like this empowers data scientists and IT professionals to build systems that don’t just work in the lab, but thrive in the real world.

Knowledge - Certification - Community